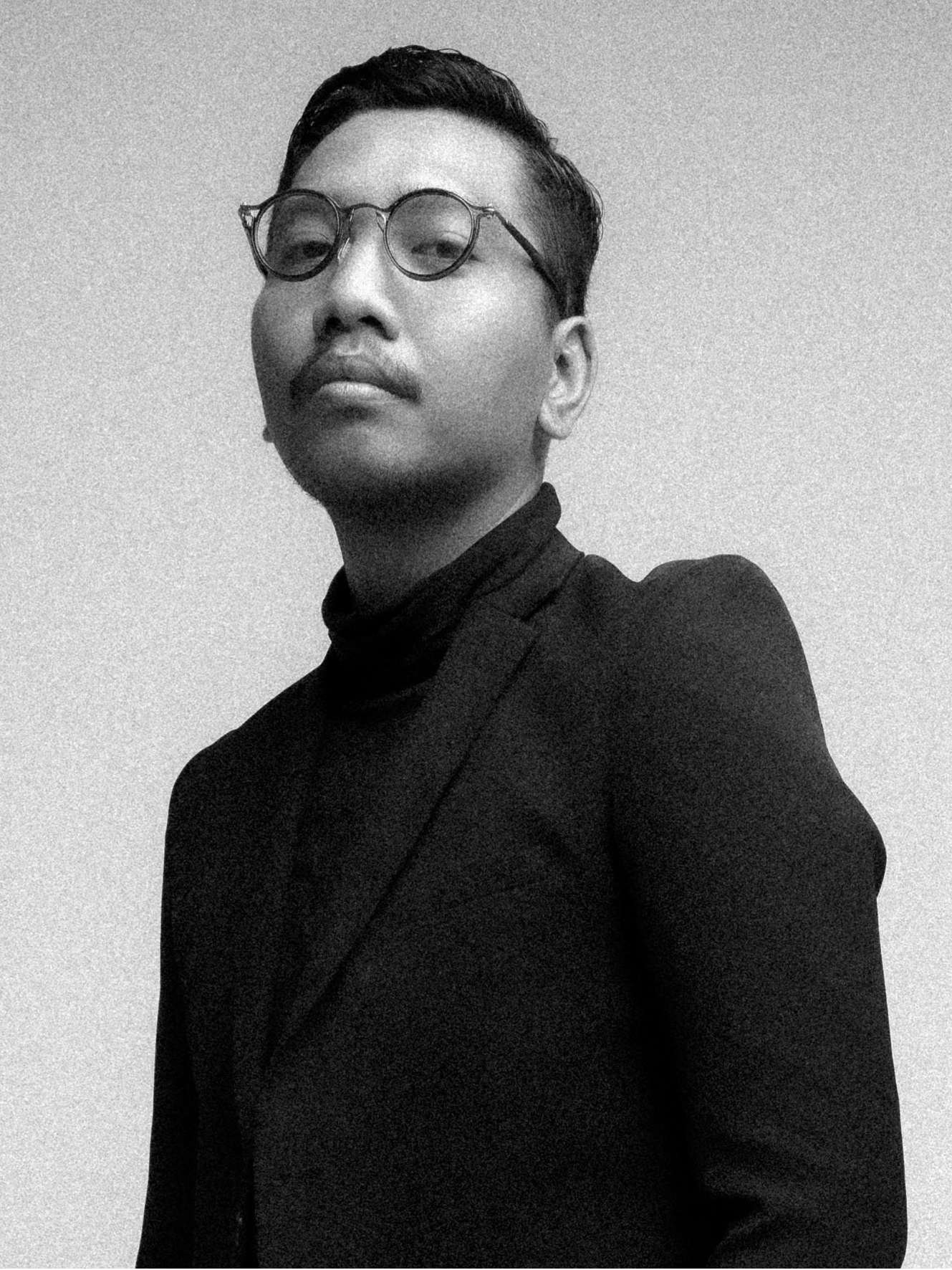

-Photo by Agung Parameswara

Project grant tittle: Preserving the Oldest Islamic Heritage Structures on the Spice Route: Wapauwe Mosque of Maluku, Indonesia Project leader: Hélène Njoto, EFEO. Text and Photo by: Agung Parameswara

The sunlight shines right over the head in Negeri Kaitetu. At 12 p.m., my watch said that the temperature was 34 degrees. However, heat does not deter the Kaitetu community from expressing their joy. That day was a historic moment. The Kaitetu Festival was held for the first time in the Wapauwe Mosque area, which is expected to be a symbol of harmony in diversity for Indonesian society.

Dozens of people dressed in white and waving red scarves chanted enthusiastically in front of the king of Negeri Kaitetu. Suddenly, the king, M. Armin Lumaela, was lifted up by young Christian inhabitants of Tana Putih, together with the people of Negeri Kaitetu. It was an emotional occasion that the people of Kaitetu will remember for the rest of their lives since it was the first time in the Negeri Kaitetu history that the King was paraded by Christians and Muslims community, particularly after the humanitarian conflict in 1999.

Kaitetu, in its many orthographic forms, is previously documented on several maps dating back to the latter part of the 17th century. Kaitetu was first documented on a European map in 1660, spelling it as "Caitetoo." This provides substantiation of its presence when the mosque was relocated from the mountain to its current position in 1664.

As early as before Europeans came, Maluku was involved in the trade of spices like nutmeg and cloves. The Portuguese and the Spanish were the first Europeans involved, but they were quickly replaced by the Dutch who controlled this lucrative trade from the 17th c. onwards. This dynamic exchange, which also brought Christianity to the region, soon spawned resistance from local communities, including populations in the Wawane mountains, the ancestral homeland of the people of Kaitetu. This conflict, which lasted about 20 years, came to be known as the Great War of Tanah Hitu. At the beginning of this war, it is said that the Old Mosque (now the Wapauwe mosque) was moved 6 km away from Wawane, to another nearby mountain site in Tehala. In collaboration with other local kingdoms, the Dutch won the war in the second half of the 17th c., and, as a result, controlled the whole of Ambon Island. Certain highland communities, like the Uli Hatunuku, who later formed the Kingdom of Kaitetu, were asked to relocate to coastal areas to simplify governance and oversight. In the case of Kaitetu, the old mosque was still located in Tehala in 1664. However, according to the M. Armin Lumaela and the elderly today, it was brought downhill "overnight, along with all its equipment." This local legend is likely to hold truth, considering the distinct "knock down" technique used in the Wapauwe mosque, in combination with its natural bindings.

The Mosque

Indonesia has the distinction of being the primary preserver of early Muslim architectural traditions in wood across Southeast Asia, starting from the 15th century. However, the country's Islamic legacy is now undergoing rapid erosion. Only a limited number of wooden mosques constructed utilizing traditional methods, such as the Wapaue mosque, are in existence at now.

"The preservation of this architectural heritage is imperative due to Indonesia's commitment to conserving and safeguarding such cultural assets". "This particular style is not limited to a single location, but rather spans across multiple regions in Indonesia, making it a potential emblem of unity in the future," said Helene Njoto, a historian researcher from the Ecole Francaise d'Extreme Orient (EFEO).

She adds that the presence of a wooden mosque with a typical architectural design characterized by overlapping roofs serves as an indication of the introduction of Islam in Indonesia. Mosques with traditional architecture are a manifestation of cultural assimilation within a certain region. This might serve as a source of motivation for the Indonesian populace to persistently strive for the promotion of harmony and cohesion among different ethnicities and religious groups.

The Wapauwe Mosque

The date of November 16, 2023 has great significance for the Kaitetu community, marking a momentous occasion in their history. A first cultural event was organized by the local community. The sacred Cakalele dance was revived after a hiatus of 14 years. Under the sunlight, drums were played. A group of women clad in white garments formed a queue in front of the Wapauwe mosque. Shortly thereafter, two cakale dancers, adorned in red color attire and draped in Cakale fabric with motifs from the Ramayana narrative, emerged from a nearby home and started their dance performance. Several women emitted screams of hysteria, with some even shedding tears, while engaging in the Cakalele dance accompanied by the lovely song Sopamea, performed by the Kaitetu young women. The song narrates the ancestral journey of the Kaitetu women, starting from their original location atop the mountain and culminating in their descent to the shore.

The Wapauwe mosque, 300 meters from the coast and Fort Amsterdam is located in the Kaitetu village, which is still used for daily religious practices. The history of the Wapauwe mosque is unknown, particularly in terms of its historical origins. Despite the mosque having undergone multiple renovations, it has maintained a singular antique form. Although the materials have been changed over the years, the Wapauwe mosque could well have been founded in the. 17th c.or even in the 15th c. in Wawane, considering the antiquity of the binding and cutting techniques, the types of materials used, its size/proportions and some local features, It is also likely that the four main posts (saka guru) may be very ancient.

One of the ancient methods that still exists is binding technique. This ancient way is distinctive and serves as indicators of the ancient mosque construction methods. Before the introduction of metallic chisels, bindings were an essential part of construction techniques. Wapauwe Mosque is a rare example of the transition from pre-chisel woodwork to joinery techniques using chisels.

Intangible Heritage: The Tukang 12

A council of men called the Tukang Dua Belas (Tukang 12) or Tukan Husa Lua in the Kaitetu language managed and took care of the Wapauwe mosque. The members of the Tukang 12 complement each other and work collectively towards maintaining customary (adat) rules and rituals. These men are chosen among the three main clans of Kaitetu, namely the Lumaela, Hatuwe and Nukuhaly. These twelve respected figures are not only craftsmen but also customary chiefs, each with his own specialty, knowledge, and duty. The Tukang 12 are keepers of sacred knowledge transmitted orally.

Though the architectural knowledge is collectively shared, the work is done following a strict hierarchy going from the Tukang Ela, the main coordinator and head of the Tukang 12, down to the Tukang Mult, who oversees communication with the Raja and the customary government. They lead the collective projects called gotong royong done by the villagers, which included Christian villagers before the 1999 conflicts and strict specifications and restrictions dictated by the Tukang 12 following customary rules. Although the 12 men complement each other, some of them, such as the Tukang Ayoul, Tukang Angkota. Tukang Sunat/Wangi and Tukang Muli, play more key roles. While the Tukang Sunat makes the first move (a cut in the protective pamal: root) allowing projects to begin, the Tukang Ayoul decides on the building and material measurements. The Tukang 12 not only regulate all forms of building projects, but they also supervise rituals and ceremonies, including Islamic ones, in coordination with the customary administration.

Traditional mosques in Indonesia represent the intricate cultural exchange that occurred along the spice routes over centuries. Indonesia is recognized as the foremost guardian of early Muslim architectural traditions in wood across Southeast Asia, beginning in the 15th century. Nevertheless, the Islamic heritage of traditional mosque numbers continues to decline, one of which is due to the increasing number of people choosing to build mosques in styles from the Middle East. Nowday, there are only a limited number of wooden mosques that have been built using traditional techniques, such as the Wapauwe mosque. Preserving Wapauwe mosque has also become an icon for peacebuilding, especially for Maluku which was hit by conflict for decades. The presence of traditional mosques like in Kaitetu may act as a catalyst for promoting harmony and solidarity among the Indonesian.